With nearly 6 million killed and 3 million internally displaced since 1988 (Consunji, 2014), the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one of the deadliest in recent history. In addition to this heavy toll, a unique characteristic of this conflict is the high revenues that armed-groups have been able to generate from the mining industry in the region. The availability of resources such as gold, cobalt and tin fueled the power struggle between warring parties, leading the conflict to last for decades. The so-called “conflict minerals” that came out of the DRC integrated the global market and were used by multi-national corporations to manufacture products like mobile phones, cars and jewelry. The opaque supply chains across the globe made it impossible to trace the provenance of minerals that ended in products now indispensable to our everyday life and consumers around the world indirectly and unknowingly contributed to the deadly conflict in the DRC.

However, the last decade has brought certain changes to the situation, with an increasing global awareness on the connection between our mobile phones and the DRC conflict. Various stakeholders started working on several levels to clean up the supply chain from conflict minerals and reduce the involuntary contribution of the global tech industry to the activities of armed groups. In the long run, those efforts could significantly help reduce the violence that the DRC population had to endure. Today, a large portion of those endeavors have already brought results or have at least been implemented. According to Kavanagh (2014), the amount of tin ore produced in DRC already decreased from 12,000 tons in 2009 to 2,900 tons in 2011. However, several years later, the situation doesn’t seem to be of the same level of priority to the public and the international community anymore, and much remains to be done to guarantee fully conflict-free minerals worldwide.

While numerous studies have been conducted in DRC on the ties between conflict minerals and armed groups, the practices of the latter, and the connection with multi-national corporations, more analysis can be done on how actors from different levels had an impact on the situation. A particular stream of initiatives, namely responsible sourcing programs, has been very popular in DRC. ‘Responsible sourcing’ is a term that has been used to categorize a wide array of projects and often remains unclearly defined. According to Brink, Kleijn, Tukker and Huisman (2019), responsible sourcing can be understood as “the management of social, environmental and economic sustainability in the supply chain through production data”. This definition includes both sourcing through sustainability schemes and ensuring due diligence in supply chains, two approaches that are often interlinked. Initiatives in the vast field of responsible sourcing have often been acclaimed for successfully reopening mines, improving the livelihood of local populations, and guaranteeing a conflict-free extraction process. However, this image was largely built by firms that had an interest in proving that the minerals they used were conflict free. In reality, major challenges remain and those initiatives often haven’t yet proven their positive impact on local populations. It is therefore important to adopt a critical perspective on responsible sourcing and discuss how current challenges could be faced. The core case to lead this discussion will be the ITRI Tin Supply Chain Initiative (iTSCi), a not-for-profit consortium that operates in DRC and supports companies to implement due diligence in their supply chain. The specific program of interest that intends to guarantee responsible sourcing is the on-site tagging system that was first implemented in 2014.

In order to assess the success of those initiatives, I will first gather information on the positive impact iTSCi claims to have made as well as any existing self-criticisms made by the organization. Success here will be defined as the initiative’s ability to impact positively local populations’ livelihood as well as its ability to extract and export minerals following fully ethical processes – with no interference by or benefit towards armed groups, no mixing with minerals from other sources, but also with good safety conditions for workers. After determining the claimed achievements of the responsible sourcing initiatives, I will discuss their limitations and possible negative impacts they’ve had on the local communities. Such criticisms can mostly be found on media sources as well as NGO reports. It is important to note there are still few critical voices or alternative narratives contradicting responsible sourcing initiatives’ claims, in part because of the difficulty to access information on the ground and because of how recent those initiatives are. Major issues that will be discussed include the contamination of responsible supply chains, the questionable sustainability of those programs, the opportunistic for-profit behaviors of some private actors, as well as the uncertain impact on local populations’ livelihoods. Finally, a handful of NGOs have given suggestions on how to improve the positive impacts of responsible sourcing initiatives, but there is still a lack of academic discussion on the matter. I will briefly discuss how stakeholders such as NGOs, the DRC government and international organizations could tackle the challenges identified and get more involved in the field of responsible sourcing.

The iTSCi: Context and Functioning

The Tin Supply Chain Initiative (iTSCi) emerged in the midst of significant changes in the DRC’s mining sector in 2010. While it had started a pilot project in one mine in eastern DRC, the initiative’s development was propelled by the nearly simultaneous signing of the Dodd-Frank Act in July 2010 and the presidential suspension of all artisanal mining activities in the regions affected by conflict in September 2010. These two events led to a sudden collapse of many parts of the local industry, from artisanal miners to traders, as international buyers withdrew and exports of tin, tantalum and tungsten officially came to a full stop in North and South Kivu and Maniema provinces (Wolfe, 2015). New regulations and the disastrous consequences of the industry’s collapse for local populations soon shed light on the need for new ways to maintain the industry while also ensuring conflict-free extraction processes (Manhart and Schleicher, 2013). iTSCi’s pilot project location was one of the few mines that wasn’t closed and could still export its minerals, and the initiative soon expanded to several provinces in eastern DRC, offering a much-needed alternative to the total ban of minerals exports in those regions. From the end of the DRC’s suspension policy in 2011, the iTSCi thrived, turning hundreds of mines “conflict-free”.

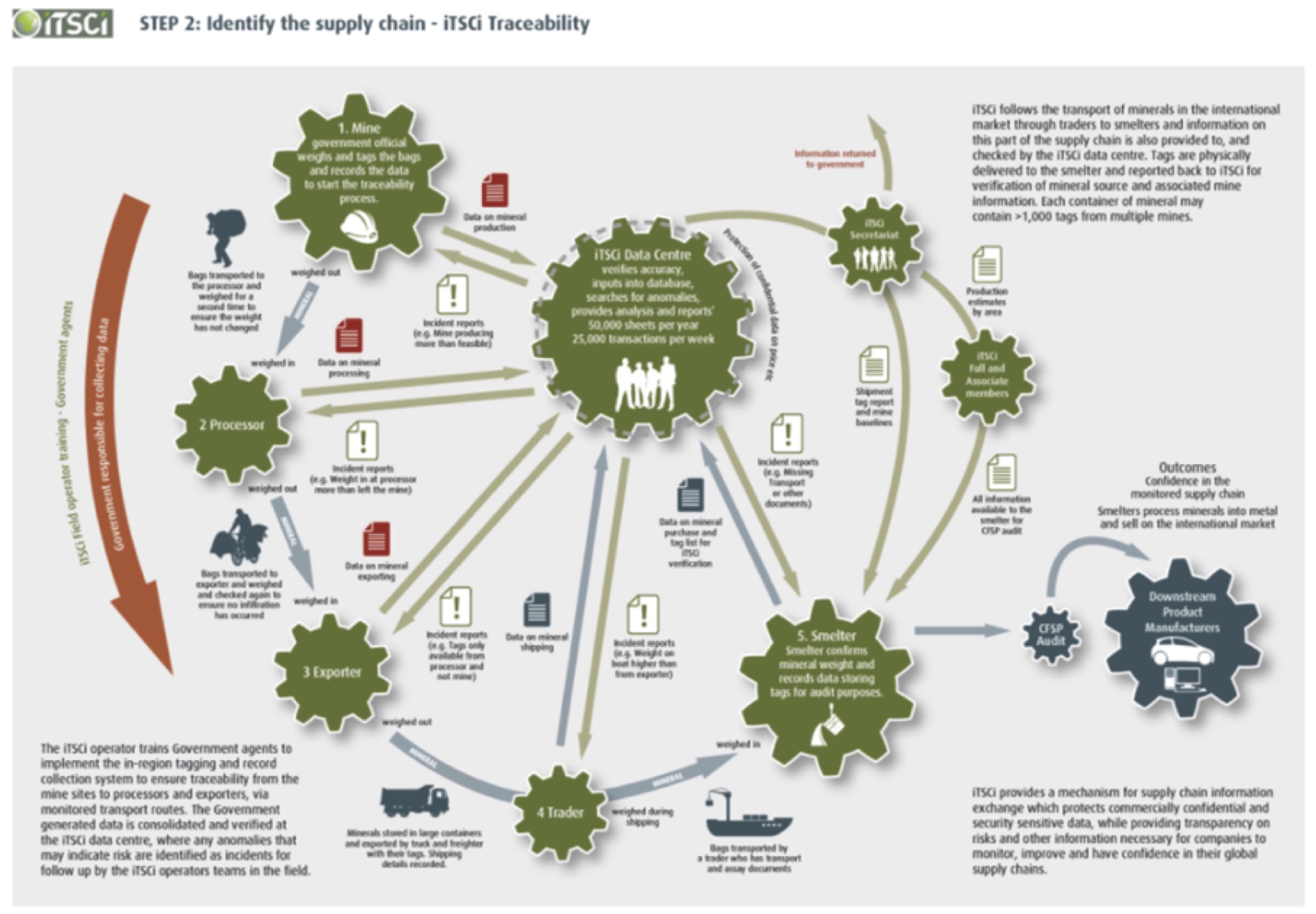

On the ground, the initiative offeres to completely ‘clean’ the extraction and processing chain up to the manufacturing level operated by downstream companies. At the level of any iTSCi-registered mine, government agents are mandated to implement an on-site tagging system. Information about each bag of tin is relayed to the iTSCi data center and then made accessible to downstream actors involved in the initiative. Tagged bags then go through all the steps of the supply chain, from the processor, exporter and trader, to smelters and downstream manufacturers. At each point of the process, bags are weighed – at entry and departure – in order to ensure the “conflict-free” minerals are not contaminated with minerals from other sources. The following infographics give a detailed description of the process (iTSCi Website).

In order to expand its network, iTSCi uses a membership system that both upstream and downstream operators can subscribe to. Downstream actors, such as Boeing, Microsoft and Intel, benefit from iTSCi’s expertise on how to apply due diligence and get access to the data on conflict-free mines and processes to ensure their minerals are responsibly sourced. Upstream members are directly involved in the creation of conflict-free supply chains and iTSCi assesses an applicant’s operations before accepting them as members. Although membership is open to any upstream operator, including artisanal co-operatives, and up to refiners, the price membership comes with a USD5,000 annual fee, and an equally high joining fee. Full members in high risk areas can get a lower membership fee of USD1,800, but still need to pay levy fees on every ton of tin exported. On its website, iTSCi explains that those fees are “set to cover costs, and vary according to local costs and tonnages”. They are collected at “only one point in the supply chain, typically the international trader” and “commercial contracts should account for appropriate sharing of the cost along the supply chain”. These fees cover 80% of iTSCi’s budget and reduce the need for funding from downstream operators (only 1% of funding sources) and other donors. The initiative is a non-profit organization and all revenues are therefore used for operations such as field implementations, traceability and data, evaluation and auditing as well as management and governance.

iTSCi also developed partnerships for the implementation of its programs. All around the Great Lakes Region, it works closely with the international NGO Pact in order to improve its impact locally. The tagging system is therefore complemented by trainings on due diligence for government agents and company staff, campaigns against child labor in mining and trainings on health and safety for artisanal miners (Hayner, 2015).

Benefits from Responsible Sourcing

The iTSCi developed in a fast-changing environment where there was a dire need to provide opportunities to populations that were out of work. There is therefore a strong consensus among all stakeholders that the initiative has had a positive impact on the region and has significantly eased the transition from the pre-Dodd Frank Act period into a new, more regulated era. iTSCi now operates in 4 countries of the Great Lakes Region (Burundi, DRC, Rwanda and Uganda). Between 2011 and 2016, it monitored 3,063 incidents related to armed groups inference, human rights abuses, fraud, corruption etc. It is currently monitoring more than 1,800 mines in the region, thus reaching and improving the lives of nearly 80,000 miners. The initiative’s social impact therefore seems well established, although it is hard to estimate its macro-level impact on the region’s stability. The iTSCi also proved its sustainability in the sectors by scaling up to a region-wide network, with more than 250 registered members in the Great Lakes region. In 2017, iTSCi reported an average of 25,000 overseen transactions per week and more than 20,000 tons of mineral exported yearly.

The initiative has also been recognized and appraised by other actors in the field as well as by scholars. Young (2015) argues that the industry has recognized the benefits of the iTSCi in creating conflict-free supply chains but also contributing to social development in eastern DRC. Local NGOs estimate that the revenue captured by armed groups from selling or smuggling tin decreased in the last decade, although a direct relationship with the iTSCi’s work can’t be established. Overall, local and international actors have largely embraced new responsible sourcing initiatives (Global Witness, 2018), and iTSCi itself is strong in its partnership with NGOs in the Great Lakes region.

The iTSCi: Limitations and Challenges

External observers on the field have identified several issues with the iTSCi scheme that threaten its positive impact on local communities and on the industry. Although those observers advocate for those challenges to be met, they don’t criticize the initiative’s existence in itself and acknowledge that it is needed in the region.

Firstly, despite of iTSCi’s elaborate system to tag and transport conflict-free minerals throughout the extraction and export process, the contamination of those ‘clean’ supply chains remains an issue. According to a field study, 42% of the bags observed in iTSCi-registered mines were not sealed with traceability tags (Matthysen, Spittaels and Schouten, 2019). In fact, government agents often attach tags to bags once they have already left the mine, further along the supply chain, as many extraction points are remote and difficult to access (Schouten, 2019). Moreover, even when the tagging does happen at the registered mines, the process may be tarnished by corruption and problematic local practices. For example, it is reportedly common for miners to store bags of minerals in their own homes while waiting for government agents to pass by their community in order to get the precious tag. Other observed practices include government agents selling their tags to other intermediaries for their own profit. Local ‘négociants’, the middlemen who buy minerals from community mines and sell them to exporters, often acquire tags through those channels and are then able to tag their own mineral bags without any oversight (Matthysen, Spittaels and Schouten, 2019). Although it is hard to assess how wide-spread those practices are, their existence threatens the reliability of conflict-free tags as it makes it possible to smuggle non-ethically produced minerals in clean supply chains.

The root cause for such practices is the lack of government capacity both at the national and local levels. The government agency in charge of supporting iTSCi is the “Service d’Assistance et d’Encadrement du Small Scale Mining” (SAEMAPE). The office was reported by Kasinof (2018) to be largely underfunded and understaffed, giving it little capacity to prevent smuggling and illegal tagging of minerals. The journalist, who interviewed officers on the field, explains that the agency often gets information about suspicious or illegal activities, such as large quantities of tin being smuggled, but doesn’t have the means to intervene rapidly and efficiently to address the problems reported to them. Because of the lack of labor force and resources, the SAEMAPE also can’t sustain constant presence across the registered mines, which explains that miners have to store the tin bags at their homes until an agent can come do the tagging process. It may also give an additional incentive for government agents to sell their tags to négotiants for them to do the tagging themselves, as they know they can’t cover all the mines themselves. The iTSCi project managers are probably conscious of those issues and, according to the iTSCi website, government agents are being trained in order to adopt better practices. However, those trainings haven’t been reported or assessed by other stakeholders and the problem of the government’s lack of capacity and corruption is likely to persist. While it can not be expected from iTSCi to solve such systemic problems by itself, the initiative should take into account those weaknesses as they cause significant loopholes in the system.

Thirdly, there is a lack of clarity regarding the exact meaning of the “conflict-free” label. According the iTSCi website, registered mines should have adopted ethical practices and be disconnected from armed-groups. However, in practice, different mines seem to have different standards and tend to focus on one element or the other. On the one hand, government officials report that they mostly assess general mining conditions (Kasinof, 2018), making sure that there is no child labor and that security requirements for workers are met, in order to give a mine the “conflict-free” label and proceed to tagging. However, as established above, SAEMAPE doesn’t have the means to prevent the smuggling of conflict-minerals and the contamination of clean supply chains. On the other hand, there are also cases of NGOs denouncing that the conflict-free tag focuses too much on ties with armed groups and leaves out ethical concerns. There is a growing counter-narrative against the commonly-spread belief that armed groups are prevalent in mining areas and that they are the main threat to the well-being of local populations. Sophia Pickles from Global Witness, a UK-based advocacy group argues that a very large majority of mines are not controlled or fought-upon by armed groups (Wolfe, 2015), but they still operate in poor working conditions. As a result, minerals could be labelled as conflict-free although they are not ethically-produced. Finally, a bag of tin ore may have been ethically-extracted and be fully conflict-free, but still have an uncertain future on the trading routes. While only a dozen out of a hundred armed groups get significant revenues from mining (Schouten, 2019), most groups fund themselves through roadblocks on trade routes, among other channels. It is unclear how much the initiative can monitor all the transportation routes used by local exporters, and there is no information on whether it is really possible to cross the region without having to pay taxes to armed groups that control trade routes. The fact that the map of the region and the location of different groups is often changing naturally renders transporting minerals and keeping them “conflict-free” even more difficult. Minerals that were extracted through a “conflict-free” process may therefore become tied to armed-groups when they are transported around the region, and it is unclear whether they lose their “conflict-free” tag if this is the case.

The social impact of conflict-free tags is also partly questionable as the system brings new difficulties to the daily life of artisanal miners. Some miners interviewed by Kasinof (2018) seem to be affected neither positively nor negatively by the introduction of responsible sourcing, and sometimes didn’t even know why they needed tags on their bags. This is explained by the fact that, even before the Dodd-Frank Act, many local firms already used conflict-free labels fraudulently in order to sell their minerals more easily. Miners are therefore used to hearing the “conflict-free” jargon and to it not having any impact on their lives. The imperfections of iTSCi as exposed in this research are likely to have given many miners the impression that nothing changed since government agents started putting tags on bags. From their perspective, corruption is still prevalent, they often still struggle to make ends meet, and minerals produced unethically still make their way in the “conflict-free” supply chains.

In some cases, local communities have even suffered as a result of the implementation of responsible sourcing initiatives. Matthysen, Spittaels and Schouten (2019) report that the new stakeholders involved in the process, such as government agents, often apply an informal tax on local miners – directly or through négotiants –, thus creating a new financial burden for households. In some cases, artisanal miners even complained of increased unemployment and poverty in their community after the implementation of responsible sourcing initiatives (Schouten, 2019). In Rubaya, eastern DRC, négotiants first purchase the mineral bags from miners and only pay for them when they are able to sell the bags further in bigger trading centers. This system is probably the result from the initial lack of confidence at the reopening of the mine that the certified bags would really be accepted further up in the supply chain. However, as a result, miners sometimes have to wait months to get paid, which puts many households that depend on mining revenues in very precarious situations. In such cases, workers often have to look for other sources of revenues and resort to criminal activities by lack of a better opportunity.

For artisanal co-operatives as well as for local companies, the costs of iTSCi membership can also be financially unsustainable. As mentioned in the presentation of iTSCi’s system, the mechanism to determine the levy taxes on certified minerals as well as the current price of such fees is not specified on the initiative’s website. However, Mahamba and Lewis (2019) reported that many operators in the industry complain about the high costs imposed by iTSCi. In December 2018, the Société Minerale de Bisunzu decided to end its contract with the initiative and to join another scheme instead. It stated that it “had no choice but to end its relations with iTSCi” because it couldn’t sustain “higher and higher costs” (Mahamba and Lewis, 2019). Rwanda Mining Association’s Chairman explains that many co-operatives and companies don’t leave the scheme by fear that end-buyers won’t accept other traceability schemes. He explains that the levy ranges from USD130 to 180 per ton depending on the mineral. In Buvaku, traders reported that they paid a USD480 tax for each metric ton of tin exported (Kasinof, 2018). In comparison, in the Kachuba mine investigated by Kasinof (2018), miners were paid around USD70 per ton collected. Although there’s no information on the costs of transporting the minerals further along the production chain, this shows that the levy imposed on iTSCi members probably represents a high cost, especially for small companies and co-operatives. Those levy taxes, coupled with the other limitations of the initiative, feed local populations’ impression that sustainable sourcing initiatives are not really intending to help them but rather acting for their own profit, just like the other stakeholders of the industry.

This perception of responsible sourcing initiatives is in fact fed by a real phenomenon. Since the expansion of the field after 2010, numerous for-profit initiatives have been developed in DRC and elsewhere, competing with not-for-profit initiatives such as iTSCi. This leads to two major concerns. Firstly, firms that provide services to clean supply chains see responsible sourcing as an opportunity for further profit and their involvement in DRC is not motivated by social, ethical or developmental purposes. This leads them to focus on firm-oriented services, such as minimizing risks for international operators by gathering data on the field. For example, the Better Sourcing program developed by RCS offers companies an elaborate data collection scheme that involves a network of agents on the field and uses an app to gather all the information and share it instantly. The priority of such for-profit initiatives is naturally not the economic and social development of local communities, which is comparatively taken into account much more by iTSCi. Responsible sourcing companies thus tend to focus on services that allow firms to claim their supply chains conflict-free and in the process gather more data on downstream operations. The second concern is that the multiplication of responsible sourcing schemes may lead to an increasing competition among both private and not-for-profit organizations. For example, the Société Minière de Bisnuzu ended its contract with iTSCi in 2018 in order to join the RCS scheme instead (Mahamba and Lewis, 2019). Having several competing initiatives will probably not be beneficial to miners and may even cause negative outcomes. It will increase the confusion of other stakeholders and may prevent not-for-profit initiatives from getting the visibility they need to get enough funding. The customers of responsible sourcing initiatives are also for-profit themselves and they are likely to be more attracted by services that put their needs of data collection first and give less attention to the needs of local communities – but surely just enough to create a conflict-free label.

Conclusion

iTSCi is facing both micro- and macro-level challenges, many of which are systemic and can’t be solved by the initiative alone. The issues reported by the media and critical NGOs are often focused on the most downstream parts of the process, while there may also be other unreported problems further up the supply chain – as iTSCi also works with smelters, refiners, and upstreams operators. Nonetheless, the greatest concern uncovered by this research relates to the transformation of the field of responsible sourcing into an increasingly competitive market with numerous private actors seeing the demand of upstream and downstream operators for clean supply chains as an opportunity for profit. Further research is necessary to assess the possible consequences of this phenomenon and to determine how the risks posed by the private sector’s rise in responsible sourcing can be tackled. This research points towards a greater involvement of other stakeholders such as NGOs, international or regional organizations, and the DRC government. Improving the capacity and resources of the latter seems like a necessary first step to tackle the challenges identified in this research. In the continuation of this reflection on possible improvements in the field of responsible sourcing, more research could be done on the role that different stakeholders can take to counter-balance the growing influence of the private sector.

Marine Krieger