Odisha is one of the poorest states in India where half of the population operates below the national poverty line. In terms of Human Development Index, it ranks 22 among 29 Indian states (1).However, it is striking that it had recorded a stunning GDP growth of 8.74% (higher than India’s GDP 8.49%) in the period between 2004-2009. This period overlaps with Odisha’s collaboration with different Multinational Mining Companies which were guaranteed rights to exploit state’s rich mineral wealth. One of such Corporations was Vedanta Alumina. It secured rights to mine Bauxite but soon came into conflict with indigenous tribal communities of the region. Here is a glance at how state, corporation and the tribal population interacted with each other amidst the mining project.

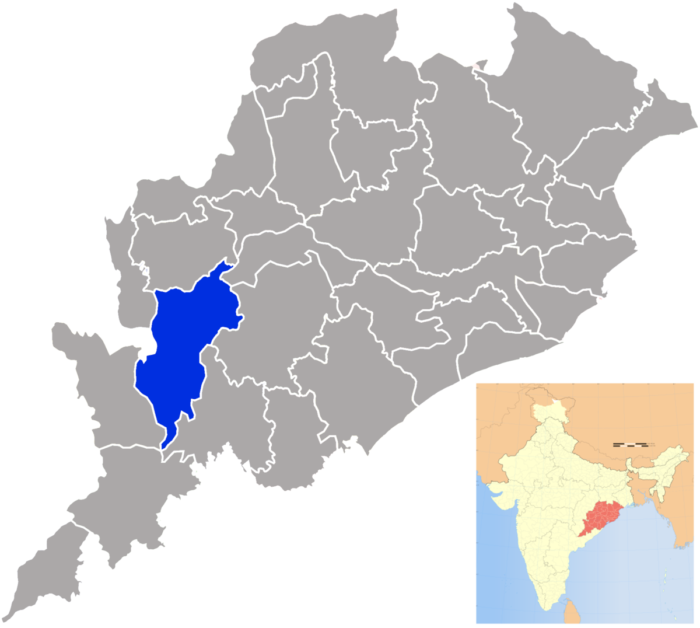

Vedanta Alumina although claimed for sustainable development and socio-economic transformation of local communities residing around the plant sites ended up displacing native tribal population from their native lands. The tribal communities lost their lands, their source of livelihood and natural wealth of their forest. At the same time, the mining site was also a sacred site, a living deity, for tribal population- Dongria Kondh. Thus, there were continuous protests by the indigenous population against the proposed project and it refused this idea of ‘development’ which was brought forth to them by the state and the company.

The ‘democratic’ state, on the other hand, provided all the ‘security’ to Vedanta to prevent any threat due to growing tension and conflict between the natives and the officials from the Corporation. In fact, there were series of legal violations ignored by the state. For instance, mining began even before the permission was officially sanctioned, the land constitutionally belonged to the tribal population, but no prior consent was taken from the tribes before passing the land rights to Vedanta. The PESA law which is supposed to ensure self-governance in tribal areas was by-passed and no penalty was sought from the company when series of environmental laws were flouted.

The community, however, continued its protest with the help of social activists and international NGOs and recently won the case against Vedanta. After about a decade of struggle to protect their rights, the tribes at Niyamgiri hill won the legal battle. Vedanta Alumina has finally issued a notice to stop its mining project in 2013.

The issue highlighted cannot be restricted to Odisha, Dongria Kondh Tribe or Vedanta Alumina. Rather, it should open debate on how should development be understood, implemented and aligned with national and community’s interests? Also, why could the tribes not protect their land despite of constitutional rights on it? What could be the role of NGOs and Activists in the tribal hinterlands to prevent any acts by state or corporations which jeopardize interests of the indigenous community?

Niti Deoliya

(1)file:///E:/Global%20Extraction/odisha%20districts%20poor.pdf

(2) Niyamgiri Triumphs, 2010, EPW, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25742009

(3) https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/oct/12/vedanta-versus-the-villagers

(4) Mining in the Niyamgiri Hills and Tribal Rights, Sahu Geetanjoy, 2008, EPW