In response to the increasing awareness about the link between mineral extraction and the financing of armed groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), various initiatives aimed at ‘cleaning-up’ the region’s mineral trade have been launched over the past decade. Most of them have specifically focused on the minerals tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold (3TG), that are crucial for the production of most contemporary electronic goods. Various companies such as Apple and Intel have therefore started attempts to certify their products as ‘conflict-free’; thereby claiming that their supply chains do not involve any minerals that are financing armed groups involved in the conflict in the DRC, a war that has become the deadliest conflict since the Second World War. Some of the most impactful changes in the DRC’s mining industry were caused by Section 1502 of the United States Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, that was passed by the U.S. Congress in 2010 and requires all companies that are registered to the U.S. stock market to release annual reports that prove that their supply chains do not contribute to the conflict in the Great Lakes Region. The law supported and influenced a variety of other regulations and standards, such as the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, and the International Tin Research Institute’s Tin Supply Chain Initiative (iTSCi), which remains one of the most prominent certification schemes of the 3T minerals until today. The general idea behind all of these initiatives is, that by regulating the mineral trade and restricting illicit actors’ access to financial means, they would reduce violence and human rights abuses (Cuvelier, Van Bockstael, Vlassenroot, & Iguma, 2014; OECD, 2016).

However, in reality, the Dodd-Frank Act and the related certification and transparency schemes came with many unintended consequences for the local mining communities. As many companies were not able to prove that their supply chains were free from ‘conflict-minerals’, they pulled out of the region altogether, leading to a de facto embargo on all minerals sourced in the eastern provinces of the DRC. Together with president Kabila’s temporary ban on all mining sites in the Kivu and Maniera provinces – in an attempt to demilitarize the area – an estimated 10’000 to 2 million miners were put out of work. By 2014, there was still only a relatively small share of mines certified due to lacking road infrastructures that made it difficult to reach mining sites in remote areas. Overall, the implementation and monitoring of certification and transparency schemes proved more difficult than anticipated. This lead to many mines either collapsing, as they could no longer sell their products, or being pushed into illegality. In some cases, local miners were even forced to join armed militias in face of lacking alternative opportunities (Cuvelier et al., 2014; Radley & Vogel, 2015).

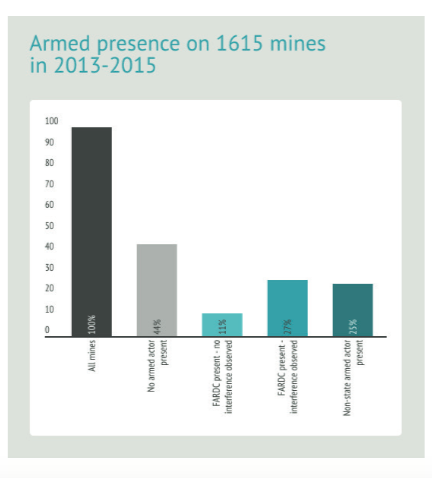

Although these initial issues were improved over the past years and more and more mines got certified, the success of these initiatives has to be evaluated with a critical eye. Indeed, especially for mines that extract any of the 3T minerals, the presence of armed groups at mining sites has slightly diminished. From 2013 to 2015, the presence of armed groups at 3T mines decreased from 30 to 16 percent. However, for gold mines, interference by armed groups remained relatively stable and mines that were affected by elements of the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) even increased. Whereas in 2013 there were members of FARDC present at 64 out of 200 gold mines, in 2015 the number increased to 84 mining sites. Overall, about 64% of gold miners had to work in the regular or permanent presence of armed actors. Altogether, by 2017, out of the 121 3TG visited mines that were affected by the presence of armed groups, 71.1% were gold extraction sites, followed by 26.1% cassiterite mines (IPIS, 2015, 2017).The fact that gold mines are significantly more affected by the presence of armed groups has to do with the predominantly informal character of the gold mining sector. By 2012, around 95% of the gold that was extracted, traded and exported was never officially registered. In 2016, the UN group of experts confirmed that gold remained the mineral that was used most widespread to finance armed groups, as it is relatively easily smuggled (United Nations, 2017). An additional difficulty to ensure ‘conflict-free’ supply chains present the various roadblocks that are used by many armed groups in the region. Even if a mining site is itself not controlled by armed groups and gets certified as ‘conflict-free’, the traded minerals might still get taxed at a road-block and thereby still contribute to the financing of violence (Vogel & Raeymaekers, 2016).

Overall, it has to be acknowledged that the different attempts to curb the trade of conflict-minerals have indeed had some positive impacts. Although the Dodd-Frank Act initially worsened the situation for many artisanal and small-scale miners due to various unanticipated effects related to the implementation of these regulations and a de facto embargo, some of these issues have been resolved over the past years and more mines were certified. For the 3T mines, this has shown a generally positive effect, with less armed actors present at the mining sites. However, the gold sector still suffers from a widespread presence of armed actors controlling extraction sites, and a comprehensive approach to address this problem is lacking. While recognising that some improvements have been made, the situation in the DRC today can by no means be described as conflict-free. Armed actors are still present throughout the region and violence has not stopped. If companies truly want to act responsibly they should not accept the status quo where they can claim that some of their mines are ‘conflict-free’, but instead increase their efforts to ensure that these initiatives are incorporated into a more comprehensive approach to resolve the conflict and bring stability to the region. Although economic objectives might have played a role in sustaining the current conflict, they were not the cause of the violence in the first place. Therefore, by focusing on a too narrow definition of ‘conflict-free, and by expecting that these initiatives present a tool to resolve the conflict, the underlying causes of the conflict remain unaddressed. Current initiatives and regulations need to be strengthened and further harmonized, whilst taking into account the interests and needs of the local mining communities in order to avoid unintended consequences that might lead to a further exacerbation of the conflict.

– Flavia Eichmann

References:

Cuvelier, J., Van Bockstael, S., Vlassenroot, K., & Iguma, C. (2014). Analyzing the Impact of the Dodd-Frank Act on Congolese Livelihoods.

IPIS. (2015). Mineral supply chains and conflict links in eastern DRC: 5 years on.

IPIS. (2017). Carte de l’exploitation minière artisanale dans l’Est de la RD Congo.

OECD. (2016). OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Third Edition (Third). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Radley, B., & Vogel, C. (2015). Fighting windmills in Eastern Congo? The ambiguous impact of the ‘conflict minerals’ movement. Extractive Industries and Society, 2, 406–410.

United Nations. (2017). Final Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Vogel, C., & Raeymaekers, T. (2016). Terr(it)or(ies) of Peace? The Congolese Mining Frontier and the Fight Against “Conflict Minerals”. Antipode, 48(4), 1102–1121.

Image sources:

http://time.com/4011617/inside-the-democratic-republic-of-congos-diamond-mines/

IPIS. (2015). Mineral supply chains and conflict links in eastern DRC: 5 years on.